Panera Painting. 2009. www.contimporary.org (defunct website)

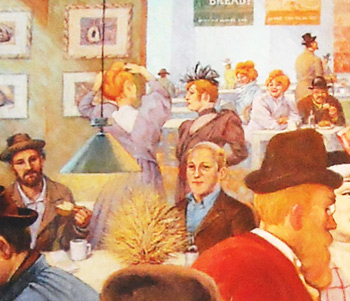

I took the above photograph at a Panera bakery-café in one of its chain locations in Columbia, South Carolina. The canvas arrested my attention because at first sight it looked as if the artist and the company had copied a famous 19th century impressionist painting, namely Paul Cézanne’s Card Players (1890-92). Upon closer inspection, however, it turned out that the picture was a mixture of ingredients and art historical personages that Panera had brought from different French Impressionist paintings. The kneading of past and present personages and objects on the wall of this restaurant suggested to me that the bakery had not been very concerned with art historical or even the plain historical truth.

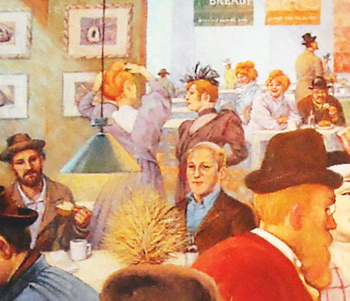

Let's perform an art historical ekphrastic ritual and quickly put into words what Panera has put on its wall in images. In the foreground two of Cézanne’s Card Players (rough men of the past) lean over what looks like a particleboard Ikea table. On its smooth plastic surface we may count, one by one, a bottle containing an unknown Panera drink, half a glass of Panera water (with two drinking straws cooling their contemporary plastic skin in ice), a sliced Panera bread loaf, a lump of butter, a painted mug containing (one might guess) Panera coffee – with all these goodies enticing our appetites from behind the tips of three or four Panera baguettes. It's a Panera Cézanne, I decided! But, hold on, consumer of culture!

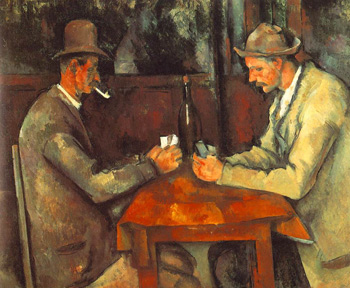

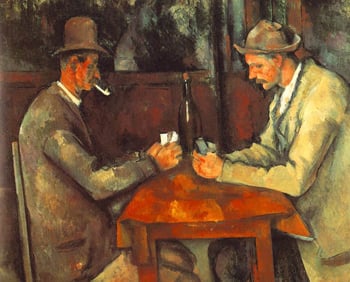

Original Paul Cézanne Card Players (1890-92)

Panera Painting, Columbia SC. Photographed in 2009

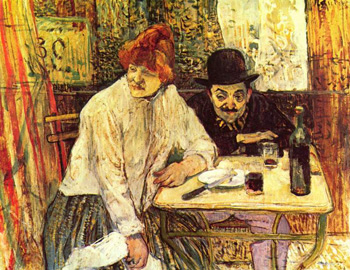

Looking closer I gradually began to realize that Panera had incorporated, within the pictorial space of its digitally printed canvas, characters from other famous works produced by the late 19th century French impressionists. Apparently, Cézanne's card players have been surrounded by pictorial personae introduced by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Look at the right edge and you will notice Toulouse-Lautrec’s half-faced (in the original green-faced) yellow-haired nightclub dancer, who may be sneaking a look at Cézanne's cards. The woman was brought in by Panera from Lautrec's Au Moulin Rouge (1982) together with other characters (including the dwarf Lautrec himself, here enlarged) leaning over their Ikea table right behind Cézanne’s card players. Now, it looks as if the Panera corporation has married Cézanne’s Card Players with Lautrec's Au Moulin Rouge – but then peering more deeply into the aerial perspective I come across another set of characters outsourced from yet another picture by Toulouse-Lautrec. Far in the background, I run into a poor copy of the “faithful Guilbert” – Lautrec’s friend Maurice Guilbert from A la Mie (1981) – who is not gazing anymore into the void, as he does in the French original, but is made instead to advertise for this company’s products, munching on a slice of Panera bread.

Left: Original Toulouse-Lautrec A la Mie, (1891). Middle: Panera fragment. Right: Woman from Toulouse Lautrec's Au Moulin Rouge (1892)

What I find interesting about this pictorial ménage à trois is how Panera has collided various art historical characters, immersing them within an atmosphere of objects and services from our ever-present contemporary world: Ikea tables, coffee mugs, electric lamps, laptops, plastic straws, Panera pictures – all veiled behind the smooth pastel palette of its chromatic corporate identity. Next to the “faithful Guilbert” and his A la Mie companion, a customer uses his laptop to ride the wi-fi waves of Panera's hotspot; next to one of Au Moulin Rouge clients a contemporary of ours – the only blue-shirted, hatless and beardless gentlemen whose contemporary cleanness and neatness makes the 19th century French monsieur next to him look like a bum – smiles at us with grave solemnity. Who knows, perhaps this is the artist commissioned by Panera who decided to self-portraitize and immortalize himself through art, or maybe he is Panera’s CEO, or perhaps the manager of that particular store in South Carolina, or just an anonymous clerk from a real estate office across the street? More research is needed.

The only contemporary businessman smiling in the Panera Painting (fragment)

I bring the corporate pictorial space to your attention, consumer and producer of contemporary art and culture, not in order to raise some traditional art historical concerns (to figure out, for instance, who is the blue-shirted gentleman who is intimidating French pictorial modernism with his respectable look), for in the end, it may turn out that our contemporary art historiography and criticism may not even accept this picture to be worthy of its scattered attention. Frankly, I decided to spend my time with it only because it seems to me that Panera wants to teach us something about the cultural logic of our time – a logic that some call “contemporary” while others, keeping with the inertia of the past decades, refer to it as “postmodernism” (a relation between periodization labels that has not yet been cleared up by learned men and women).

Paneran pictorial space claims (like the liberal spirit of our time) to be democratic and egalitarian. I look at that wall and my mind tells me: Welcome to Panera! Everybody’s welcome! We don’t care if you’re old or young, French or otherwise, famous or not, bearded or beardless, clean or poor… Y’all come have a cup of joe! But this egalitarianism also makes its presence felt on a temporal or historical level – French impressionists and us, we are all equal, we are all contemporaries. Indeed, if let’s say 2000 years from now, some future archeologists of knowledge will want to figure out in what particular time or historical period the personages of this unearthed canvas assembled themselves, they may run into difficulties. On its surface they will see types and fashions that do not seem to have inhabited the same phase. The temporality of the picture may appear puzzling to them, unless they themselves inhabit a time as ahistororical as ours. The temporality of this Panera picture may appear to them more reminiscent of ancient Egyptian and Babylonian iconography (4000 years earlier). They may even decide that those in whose time the picture was produced had a non-eschatological understanding of time; or that they (that is us) even professed a cyclical view of time according to which the accurate historical past is totally irrelevant, and that our destinies are controlled not by some beliefs in the progressive movement of the human spirit but by a mysterious cosmic balance which is maintained here on earth by the pharaohs of Wall Street and the fast food industry.

On a pictorial level the Panera painting is also interesting, for it differs from what we have been used to see in the history of art. This becomes clear when we compare it to a modernist collage (even though Panera does not resort to a literal “cut and paste” but applies a sort of contemporary art appropriation). Back in the era of what critics call high-modernism (that is before WWII) artists also appropriated and blended images. They mixed them to construct new emancipatory meanings. But their future or utopia-oriented modernism did not permit them to mix their present with their past, for the latter had to be transcended, had to be broken with, for a brighter future. Take revolutionary avant-garde collages: the French Cubists collaged guitars, bottles, pipes, newspaper scraps, fractured war news of their time that they read in the Parisian cafés (Picasso); the German highly political Dadaists collaged distorted faces, repellent mugs of German militarist generals, hi-tech tanks and cannon barrels, bodies wounded by the modern war that wandered in the streets of Berlin (Hannah Hoch); the Russian avant-garde tried to construct new meanings by blending cows, saws, knives, scissors, airplanes, clocks, chopped words and splintered syllables (Malevich) all blended up in order to express Russia's desire to enter the modernity of its more “advanced” neighbors.

The radical modernists did not blend their present with their past. It is very difficult to imagine the future-oriented historical avant-garde collaging personages who lived 100 years earlier or objects from some distant past (a pre-Gutenberg scroll or a steam engine from the time of the industrial revolution). Neither did they – God forbid! – copy artistic characters made by other famous painters of the past – even though some exceptions may be found in surrealism, but then again the surrealists did not copy but took the scissors and cut up all the damned venuses and medias of the past, replacing their pretty faces – for the fun of the revolution of the mind – with lizard heads. No Copying or Appropriation! And this was at a time when nobody cared yet about the ® and the © of the contemporary copyright industry and its “intellectual property” assets.

Thus in the modernist or avant-garde collage the present collides with the future, and all in the hope for a brighter world. In our contemporary art and corporate culture the present seems to enter into constant dispute with the past, as if that “end of history” declared a few decades ago by an employee of the US State Department had indeed come to pass.

Of course, some of you will rush to tell me that this is all the fault of the culture industry and that I cannot (I do not in fact have a moral right to) compare a unique Picasso to a digitally produced Panera multiple – even though I could go around and bring you examples from legitimate contemporary art that deploy the Panera artistic device and method, for where else could the bakery have learned about “appropriation?” And others of you will tell me that contemporaneity is narrative-less, or rather as critics of postmodernism have suggested it gathers fragments of narratives, disjointed sentences, schizophrenic disjunction or écriture, heaps of language. Most importantly…