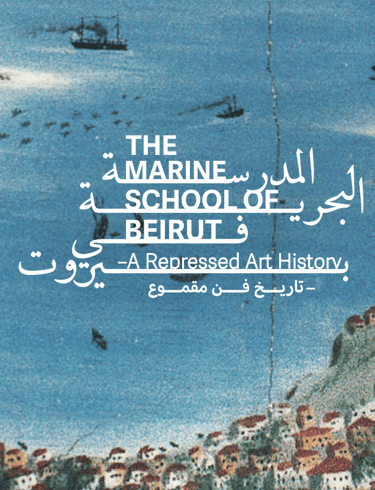

The Marine School of Beirut—A Repressed Art History

FALL 2022 (AUB Byblos Bank Art Gallery, Beirut)

November 1, 2022—March 1, 2023

This project focuses on a group of painters active in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the Ottoman Middle East. And even though some of the paintings on display are well known, there has never been an attempt to exhibit them under one stylistic canopy, or as part of one painterly tradition.

In the past decades, art historians and connoisseurs who sought to offer a more comprehensive account on the history of art in Lebanon, Syria, and the Levant, have called attention to a “Marine School” (also sometimes the “Maritime School” or the “School of Beirut”). The Lebanese painter Moustafa Farroukh (1901-1957) may have been responsible for launching the label when he presented the results of his research into the “precursors of Lebanese art” in a conference organized by the Cénacle Libanais on March 28, 1947. In his presentation Farroukh names Ibrahim Serbai, Dimashqiyah, Said Merhi, and Ali Jamal, all of whom – he says – “devoted their art to paint boats, natural scenes and the sea.”1 One may also assume that the label “Marine School” – which stuck with the later generations of art historians – took root when Farroukh states in the next paragraph that Ali Jamal, “whose passion for painting the sea and its waves and boats led him to leave for Constantinople where he joined the Naval [or Marine] School and graduated as naval officer.”2

Was this the beginning of the mysterious art historical category that the present project seeks to unravel?

After Farroukh’s presentation at the Cénacle, art historians began to mention the Marine School as a “class” that gathered a particular category of painters, pointing to the specifically Sunni character of this painterly tradition. Indeed, most of the painters associated with the label were Sunnis, and a few were Greek Orthodox. But it was not only due to Farroukh (himself a Sunni) – or to the fact that Beirut was in those days predominantly inhabited by Sunnis with a minority of Orthodox Greeks – that the Marine School has been associated with Sunnism.

The so-called Marine School can be viewed as part of a larger cultural phenomenon, with groups of painters dispersed throughout Ottoman Turkey. What united them was, first, a common pictorial language constituted during the modernization reforms within the Ottoman Empire, especially the reforms linked to education. Several military, engineer, and naval schools based on Western principles of education were opened in Constantinople throughout the nineteenth century. In these academies, which were part of Ottoman Sultanate’s westernization reforms, the cadets did not only study fortification, cavalry, sword and rapier, but also topography, architecture, cartography, and drawing. These military schools taught the basics of painting and drawing not for art, but for technical or defense purposes of the Ottoman state. It was a French painter, René Huyghe, who “christened” some of the painters he encountered in nineteenth-century Constantinople with the label “Turkish Primitives,” and which included many sub-categories such as: “Soldier Painters,” “Painters of the Sea,” “Photo-realist painters,” Darüşşafaka School,” and others.

The Marine School of Beirut can be understood as a local manifestation of the “Turkish Primitives.”

Not all painters of the Marine School of Beirut and/or Tripoli were trained in the military, naval, and engineering schools of Istanbul. Those who were self-taught, or schooled in Beirut, or in the capitals of other vilayets, they adopted pictorial conventions common at the time throughout the Empire. This exhibition does not only wish to display a constructed art historical category, and a partially lost art historical phenomenon, but also to show what has survived from it. Using the metaphor of the sea, we can discern what remains at the surface – that is, the few paintings that are still available in various local collections – and suggest what lies at the bottom, that is, paintings that once were part of the tradition but have been lost or destroyed or are not currently available in Lebanon. For the latter we rely on digital files.

The project addresses, finally, the relevance of the Marine School for the art history of Lebanon and the region. Art historians and connoisseurs often mention the “hidden” aspect of this pictorial tradition, referring to a dearth of scholarship. We agree, but prefer to use the term “repression” instead, believing that this dearth or invisibility is the result not of innocent ignorance or lack of knowledge but comes as a result of historical processes and internalized conflict. The tradition has been pushed to the bottom by the dominant art historical narrative according to which the so-called “forerunners” (Daoud Corm, Khalil Saleeby, Habib Serour, Philippe Mourani, Youseff Hoyek, Gibran Khalil Gibran) brought art from Europe, at a time when other cultural processes (like early Ottoman-ear painters associate with the “Marine School”) have been sunk to the depth of history.

Read the full version of this text in the exhibition publication.

Octavian Esanu

1.For an English version of Farroukh’s 1947 presentation at the Cénacle Libanais see “Pioneering Lebanese Artists—Moustafa Farroukh,” The Monthly (December 10, 2015), https://monthlymagazine.com/article-print_1821_print (Accessed September 25, 2022).

2.Ibid.

Download Publication