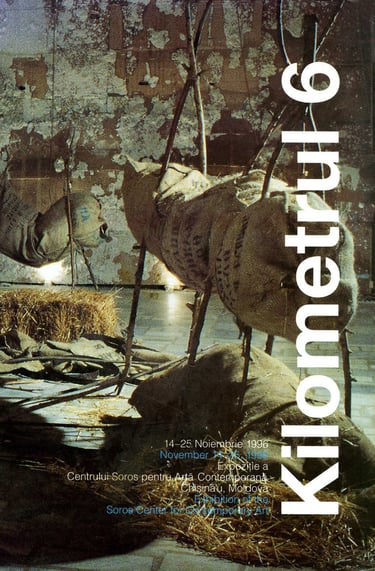

Kilometru 6/The 6th Kilometer (First Annual Exhibition of SCCA Chisinau)

1996 SCCA, Center for Contemporary Art, Chisinau Moldova

Download Catalogue

The first annual exhibition of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art (Chișinău) opened on November 14, 1996 in the main exhibition hall of the Union of Artists of Moldova under the title Kilometrul 6 (The 6th Kilometer). Most of the participating artists had already been part of the Carbonart 96 artist camp, and a few of the exhibited works were in fact produced during that summer retreat (see Carbonart 96). For this first annual exhibition, the SCCA rented the Union of Artists’ main exhibition hall, and commissioned works by way of offering grants to a select group of Moldovan artists. The latter were intended exclusively for the production and display of works of contemporary art, as this phrase was inscribed in the name and the mission statement of the newly established art center. The selection of artists was made by the curator and staff and approved by the SCCA Chișinău “Advisory board,” in full accordance with the equal opportunities policies established by the Open Society Institute and the regional director of the SCCA Network.

SCCA Chișinău opened its office in the spring of 1996. This center for contemporary art was part of a larger system of centers which together formed the Soros Centers for Contemporary Art (SCCA) Network. The Network had been a regional project of the Open Society Institute launched by George Soros and the Soros Foundation in most of the postsocialist countries and republics of the former USSR. Its mission was not only to modernize artistic discourse by encouraging the most innovative art forms, or by facilitating access to information about the most recent Western art, but also to promote artists and help them join Western art world circuits and markets. The SCCA Network, which grew out of a small documentation program initiated in Budapest, Hungary in 1985, spread out widely during the 1990s, leading to the opening of eighteen SCCAs in most of the administrative or cultural capitals of the countries once behind the Iron Curtain. The activities and budgets of these centers were structured according to major categories including the Documentation program, Grants for Artists and the SCCA Annual Exhibition. While the Documentation Program allocated a special budget for the research, collection, documentation and the production of art historical knowledge of local artistic practices and artists (especially of those known as “unofficial art” under socialism), and the Artists Grants program offered artists monetary support (mostly for such promotional purposes as participating in international art exhibitions, producing a catalog, or photographic and video services and the making of artist portfolios), the main goal of the Annual Exhibition was to showcase a range of artistic media that were not sufficiently explored within local artistic scenes. Most of the annual exhibitions, therefore, organized throughout Eastern Europe during the 1990s by the SCCA Network, also showcased a wide range of the newest Western consumer electronics, computers and telecommunication equipment, via video art, computer art and multimedia, ephemeral artistic practices relying heavily on computer documentation. The director and the staff of each center were encouraged to seek technical partnerships and sponsorships from local vendors of Western electronic equipment and providers of communication services.

The organizers chose the title The 6th Kilometer in order to suggest that the exhibition’s main goal was to put on display art forms that had appeared in Moldova six years after the proclamation of its sovereignty in 1990. This former republic of the USSR had no strong tradition of unofficial art – and, unlike many other SCCAs in the network, neither the staff of the SCCA Chișinău, nor the artists engaged in its first events (with a few exceptions), had been regularly exposed to or were part of any unofficial art grouping. Instances of aesthetic resistance to socialist realism were articulated on canvases, but were quickly compelled to seek more liberal artistic milieux in Moscow, Leningrad or the capitals of the Baltic republics (Mihai Țăruș and Iurie Horovschi serve as good examples). With the collapse of the USSR and the proclamation of independence, the inertia of the local artistic scene led it to assert its originality primarily in pictorial terms, by resorting to formal or self-referential abstraction. When referentiality was invoked, it was articulated in terms of a nationalistic critique of the Soviet project; any initial forays into non-fine-arts and/or conceptual idioms that might have made a previous appearance still await documentary and art historical investigation. Most importantly, works in the so-called “postmedium condition” (that is, artistic explorations of digital, electronic and communication technologies or ephemeral art forms) have been largely absent. Therefore the SCCA Chișinău saw its primary task in accelerating the pace by encouraging artists to tackle the new artistic media, knowledge of which started to arrive together with the Western art magazines brought over by American and Western European private and governmental agencies and foundations.

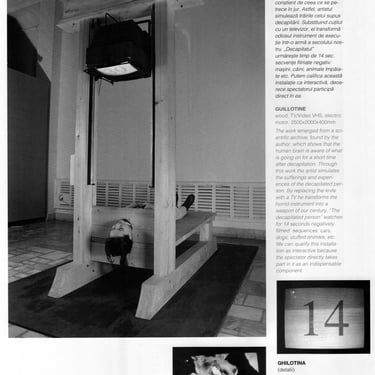

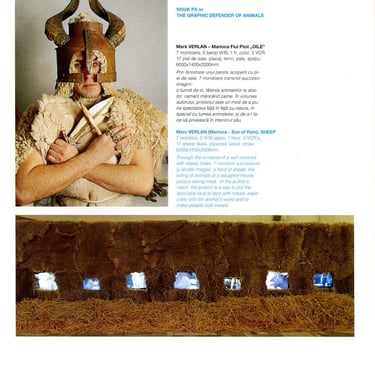

The 6th Kilometer was the center’s main event of 1996, and an opportunity to present to the public the latest forms of local “contemporary” artistic production. All the artworks – with the exception of a few performances – were specifically commissioned for the exhibition and fully supported from the Annual Exhibition budget of SCCA Chișinău. The exhibition was very widely attended, with viewers completely filling the main hall of the Union of Artists. Many in the audience were bemused to find at the opening an artist giving free haircuts to those who needed or desired one (Mark Verlan, Free Haircut); a life-size guillotine whose blade was replaced by a TV set that showed violent images from one of Chișinău’s abattoirs (Iurie Cibotari, The Guillotine, Figure 5.10); a painting made from dirt, sand, and glowing neon tubes that in the artist’s understanding mixed the lasting patina of local tradition with the translucent quality of contemporary advertising (Igor Scerbina, Metaphysical Painting). On the occasion of this exhibition a conference was organized under the title “The Open Work,” inspired by Umberto Eco’s 1962 Opera Aperta.

The reaction of viewers and the press to this event was mixed. While some called the artists and the exhibition organizers “buffoons” paid by a rich American to entertain the destitute local crowd, others, and especially guest art critics from Moldova and Romania, acknowledged the importance of this event, seeing in it the beginning of a new chapter in the history of the local visual arts. Within a wider context, and from the curator’s and organizers’ perspective, it soon became clear that contemporary art – as it was promoted and funded in Eastern Europe by various Western funds during the 1990s – was also a way of measuring the success of the transition from socialism to market democracy, a transition towards a new image envisioned in terms of an “Open Society,” to recall the title of Karl Popper’s work, used as a handbook for setting in place the policies of the Soros Foundation. Moreover, contemporary art as practiced in the postsocialist countries at that time also had a distinct ethnographic quality to it. This was soon learned from the export of Moldovan contemporary art to various international venues where it was expected to prove the success of the “democratic” transition. For instance, The 6th Kilometer’s most praised installation, The Guillotine has become the success story of SCCA Chișinău, having been requested and sent on multiple occasions to represent “Moldovan contemporary art” at various exhibitions in the West. This ethnographic quality was an important feature of contemporary art at that time, and it is still noticeable in certain Eastern European or other non-Western regions of the world. A term deployed by the leader of the Collective Actions group in Moscow, Andrei Monastyrsky (which Monastyrsky used specifically with regard to the practice of Moscow Conceptualism, but which can be extended to the wider postsocialist context) is particularly relevant. The term is “local-lore-ness” (kraevednost’), referring to a common practice in the 1990s, when conceptual art from Moscow was shown in Western exhibitions not under the generic term “conceptual art,” but as exotic instances of something called “Russian conceptual art.”[1] This specificity – be it “Russian conceptual art” or “Moldovan contemporary art” – indicated that these works were seen as a contribution not to a universal contemporary practice common in the late twentieth century, but as a distinct and distant specimen of such a practice that only resonated within a certain artistic context far away from the Western art capitals. This showed the asynchronous character of postsocialist art, its contemporaneity (to use Terry Smith’s words) contemporaneous only with itself[2] and the particular context where it emerged; not yet a global contemporaneity of artistic means and forms, if the latter were even possible.

[1] For kraevednost’ [local-lore-ness] see Andrei Monastriski’s Slovar’ terminov moskovskoi kontseptual’noi shkoly (Moscow: Ad Marginem, 1999). For an English translation of this Dictionary see Appendix in Octavian Esanu, Transition in Post-Soviet Art: The “Collective Actions” Group before and after 1989 (Budapest: Central University Press, 2012), 315.

[2] Terry Smith, What Is Contemporary Art? (Chicago IL: Chicago University Press, 2009).

Fragment from "CarbonART 96 and The 6th Kilometer, SCCA Chișinău 1996" in Esanu, ed. Contemporary Art and Capitalist Modernization.