JPEG DEVOURING ITS OWN PIXELS (a story)

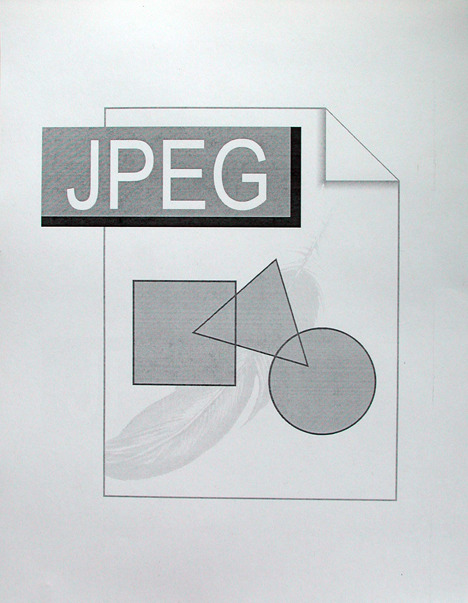

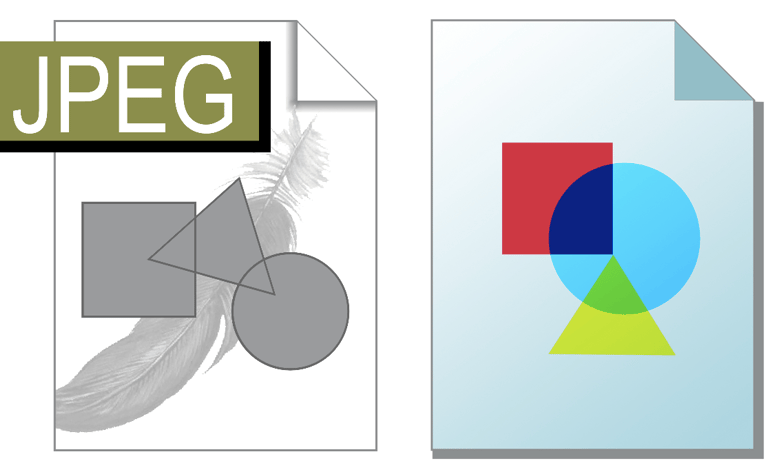

The above two icons represent the image file formats in two mainstream operating computer systems. On the left, there is the default symbol of the JPEG file format, employed by the Apple corporation in their Mac OS X operating system, and on the right is the symbol of a PNG file, used by Microsoft in Windows XP. What may be the relation between these file icons offered by default to every user of a personal computer and the history of modern art? In order to make things more simple lets ignore Microsoft’s PNG and focus instead on the JPEG file symbol employed by Apple (the operating system that I am using for this project).

JPEG (an abbreviation that stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group) has been the most popular method for compressing, storing and transmitting pictures in today’s image-saturated world. Both as producers and consumers, we deal with millions of JPEG files. Taking a picture with a digital camera or a mobile phone, processing this image in one of the editors, sharing it with friends via social or other networks, surfing the web, reading the news, watching television, bumping at every corner into advertising, and so on and so forth: most of the image information that one encounters today is stored by default in one or another available JPEG formats. The JPEG files are thus the building blocks, the primal elements of our spectacular specular world; they seem to be the invisible and indivisible monads that constitute and sustain today the matrix.

But let’s reflect a little bit upon how these files are symbolically depicted. Both Microsoft and Apple represent their most popular image formats by means of a a and a . Under both, Mac OS and Windows operating systems, the image files icons are depicted by means of primary geometric figures. In Mac OS case, the square, the circle and the triangle are imposed on a feather – a symbolic representation, which may suggest that Apple Inc., sees a direct relation between these abstract geometrical figures and the “natural” objects from our everyday recognizable world. Stated in a slightly different way, it may be said that if one is to disassemble our visual virtual world into its primary elements, every image would then be stripped down to squares, spheres, and triangles. Unlike the matrix reality, which in the movie seems to be generated by a combination of zeroes and ones (a binary numeral system), an alternative “visual” understanding of the matrix that we inhabit may be also possible by means of a ternary logic, one which draws not upon numeric values but upon primary geometric shapes.

Here we arrive at art history. The division of the visual into primary elements has been regarded as a turning point in the history of modern art. It is well known, for instance, that Cézanne advised his younger colleagues to treat nature “by means of the cylinder the sphere and the cone” – a piece of advise that has had a great consequence for the next generation of French painters, especially for those who contributed to the rise of Cubism. But the advice went far beyond the borders of France. In the pre-Soviet Russia, Malevich, (fully acknowledging Cézanne) had performed a similar painterly reduction distilling the artistic canon into primary elements symbolized by the square the circle and the cross. If Cézanne taught to treat nature by means of the cylinder, sphere and cone – a tripartite volumetry that was still attached to a three-dimensional illusionist mode of representation – Malevich went further reducing art and nature to three flat or two-dimensional elements: the square, the circle and the cross or the cruciform.

In Malevich’s case these three geometrical elements play also a wider symbolic function, for the square represented his cubist phase, the circle the futurist phase, and the cruciform stood for his transition into Suprematism: a new method that was understood by the painter as a dialectical outcome of his Cubist and Futurist experiences – that is of his engagement with the Russian Cubo-Futurism. It must be noted that he had also replaced Cézanne’s cone with the cruciform, for reasons which may have to do with his almost religious belief in the future of Suprematism – his gift to the world.

At the origins of this big sdvig (shift) towards Suprematism stood the Black Square, whose significance Lissitsky explained in the following way: “[…] Malevich exhibited a black square painted on a white canvas. Here a form was displayed which was opposed to everything that was understood by ‘pictures’ or ‘painting’ or ‘art.’ Its creator wanted to reduce all forms, all painting to zero. For us, however, this zero was the turning point. When we have a series of numbers coming from infinity …6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, 0…it comes right down to the 0, then, begins the ascending line 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6…” (1)

The Black Square, which collected such epithets as “the royal infant,” “the zero of form,” “the nothing of art,” is then like the neck that connects the two bulbs of an hourglass: the art of the past passes through it emerging in the other bulb purified, changed and highly modern. The impact of Malevich’s Suprematism on the 20th century art and design cannot be ignored. Without the new pictorial language of Suprematism, as well as without other contributions by various representatives of the historical avant-garde, one can hardly imagine the iconography of the dogmatic Socialist Realism drafted behind the Kremlin walls in Moscow, nor the mercantile glossy imagery sold by advertising industry after World War Two on the Madison Avenue in the New York City.

Thus when speaking about the symbolism of the JPEG file it is worth keeping in mind both Cézanne’s and Malevich’s painterly reductions, for here one may see in the square, circle and triangle of this icon, the contributions of the cubists, futurists, suprematists and many other “ists” who had revolutionized the visual language during the twentieth century, contributing directly or indirectly to the current pictorial canon and modes of representation. The JPEG file is the numbers 6 or 7 in the ascending sequence proposed above by Lissitsky, when he talked about the significance of Malevich’s Black Square. One may even say that for contemporary artists of today the JPEG file is the primal constituting element of a petrified and arrested culture; it is today what once was for Cézanne and Malevich the realist or naturalist modes of representation (the landscape painting for instance) based on Renaissance perspective and the faithful mimetic copying of reality. But one may then wonder how to perform today another painterly reduction of the imagery built from JPEG files, from files that have flooded our real and virtual worlds with invisible squares, circles and triangles? How is it possible to further decompose or negate this language?

Part I: Prelude

Left: Default icon for JPEG file under Mac OS X. Right: Default icon for PNG file under Windows XP

Part II: JPEG DEVOURING ITS OWN PIXELS

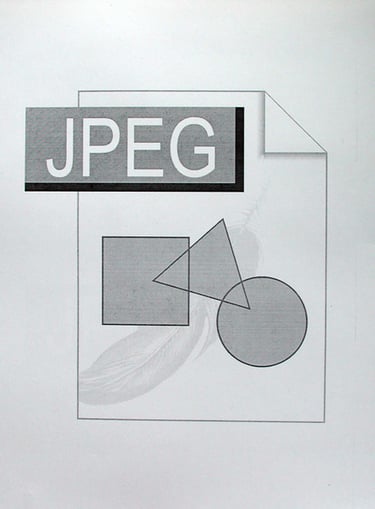

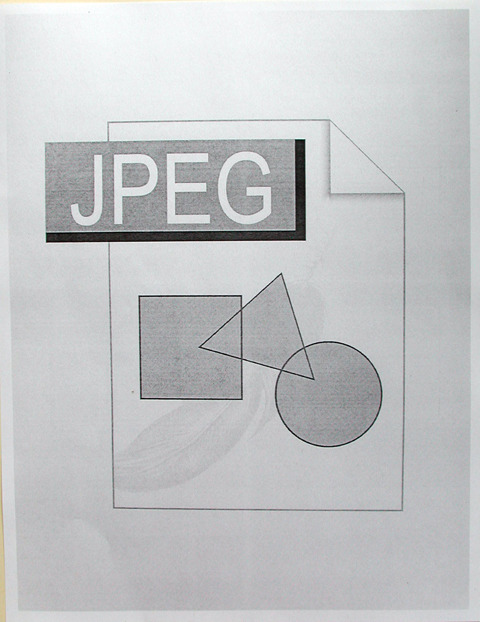

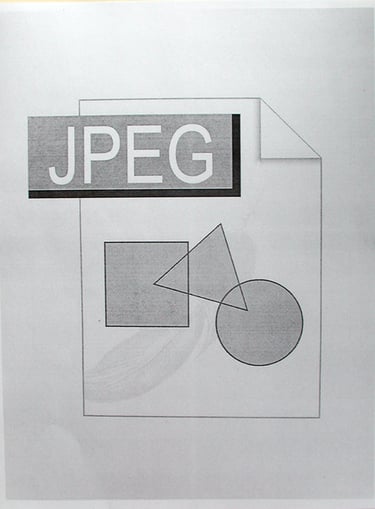

The sequence of images that follow is the photographed icon of a JPEG icon. The square, circle, triangle symbol was first printed then photographed with a digital camera and then printed again. This operation is performed multiple times, in order to observe what happens to the digital square, circle and triangle when it is treated digitally.

Notes:

1. Simmons, W.S., Kasimir Malevich's Black square and the genesis of suprematism 1907-1915. (New York: Garland Pub., 1981), 319.