The filmmaker, screenwriter, film theorist, artist, and political activist Adachi Masao (b. 1939) is considered—along with Koji Wakamatsu and Nagisa Oshima—a leading figure in Japanese New Wave Cinema. Since the 1960s, Masao has produced many experimental films and written film scripts on a range of political topics. In the 1970s, Masao joined Nihon Sekigun, the Japanese Red Army (a communist group founded by Fusako Shigenobu in Lebanon in 1971), for the purpose of supporting the Palestinian struggle. After a trip to the Cannes Film Festival, Masao and Wakamatsu stopped in Beirut to interview and film Palestinian fighters. Masao declared himself a militant for the World Revolution and the Arab cause. He then spent 27 years in the Middle East: for the most part in the Bekaa Valley and, after the withdrawal of the Red Army from Bekaa in 1997, in Beirut.

There is little information about this period of Masao’s life. He claimed to have worked on several projects, but all film material was destroyed during air strikes. In 1997, Masao, along with four other members of the Japanese Red Army, was arrested. The arrest—which the newspapers of the day saw as part of the U.S.-sponsored Middle East peace process, and the Lebanese government’s intention to boost its international image—provoked a wave of indignation among Lebanese and Palestinian leftist groups, university students, local intellectuals, government ministers, and religious leaders. The arrest also mobilized, according to different accounts, from 100 to 160 attorneys, who declared their intention to be part of the defense team. In the end, the team was reduced to 50 lawyers due to the space constraints of the courtroom. Beginning in 1997, Masao spent three years in Roumieh prison in northern Beirut for passport forgery, illegal entrance, and residency in Lebanon—accusations he categorically denied in court. Due to the absence of an extradition treaty between Lebanon and Japan, he waited several years in a legal limbo until the completion of the juridical procedures. While in prison, Masao converted to Orthodox Christianity and married; he also practiced acupuncture and produced a series of drawings. In 2001, he was extradited to the Japanese authorities. Local media explained the extradition, and its timing, as part of the Lebanese government efforts to secure much-needed resources and investments for post–Civil War reconstruction from the USA and Japan.

AUB Art Galleries opens its current exhibition, Cut / Gash / Slash—Adachi Masao—A Militant Theory of Landscape, with the aim of reintroducing Adachi Masao to the Lebanese public following his eighteen-year absence from Lebanon (2001–2019). While his name may sound familiar within certain Arab political and cultural circles, Masao’s art, films, books, and film theories are much-less known or studied. In addition, the exhibition seeks to introduce Masao’s films and theory of cinematic landscape into AUB’s academic community and curricula. Specifically, the exhibit brings to the public and students’ attention the so-called discourse of cinematic fukei-ron (literally “theory of landscape” in Japanese) that emerged in Japan at the end of the 1960s. Masao was one of the main contributors and practitioners to the theory.

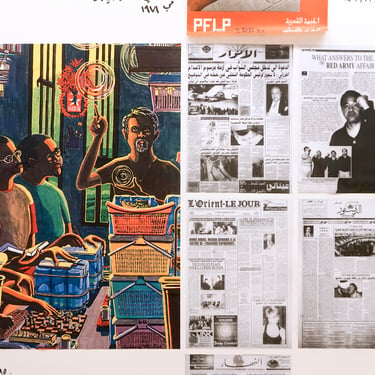

This exhibition highlights two of Adachi Masao’s major films: A.K.A. Serial Killer (Ryakusho: Renzoku Shasatsuma, 1969), which is a classic example of cinematic fukei-ron, and the propaganda newsreel The Red Army / PFLP: Declaration of World War (Sekigun-PFLP: Sekai Sensō Sengen, 1971). Additionally, we show Masao’s drawings, books theorizing fukei-ron, photos by the renowned photographer and critic Nakahira Takuma (1938–2015), posters produced by Japanese Neo-Dada artists of the 1960s Genpei Akasegawa (1934–2014), and a documentary shot by Joji Ide of Juro Kara’s Jokyo Gekijo (The Situation Theater) performances in Lebanon and Syria in the 1970s. Additionally, four other films by Adachi Masao are screened: Yûheisha–Terorisuto (The Prisoner, 2006), Bowl (1961), Galaxy (1967), and Female Student Guerrillas (1969). Lastly, we have put together an improvised collection of texts by or about Masao—which have been selected from a large body of writings in Arabic, French, Japanese, and English and written during different decades—as well as more specific writings on the theory of landscape by Masao Matsuda—which we have translated into English for the first time for this project.

Octavian Esanu

* For the full version please click here

Cut/Gash/Slash—Adachi Masao—A Militant Theory of Landscape

SPRING 2019 (The Rose and Shaheen Saleeby Museum, Beirut)

Download Publication

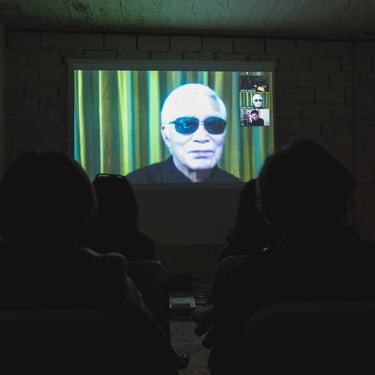

Watch Interview with Adachi Masao