CarbonART 96: Summer Camp for Artists

SCCA-Chisinau, 1996. Sadovo, Calarasi Moldova

Download Catalog

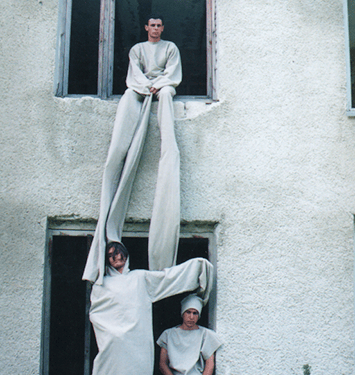

The artist colony called CarbonART took shape in the summer of 1996 in an abandoned Soviet Young Pioneers summer camp near Sadova (Călărași, Moldova). CarbonART 96 was first of its kind in Moldova, and even though “artist camps” or literally “camps of creation” (as these artist retreats or colonies were often called: tăbără de creație in Romanian, or tvorcheskii lager’ in Russian) were fairly common in the USSR and other socialist and non-socialist states, this one differed in specifically targeting and inviting “artists who worked with new concepts and modes of artistic expression,” as the newspaper ad posted by the organizer – the recently founded Soros Center for Contemporary Art (SCCA) Chișinău – stated. The SCCA Chișinău rented the Young Pioneers camp, providing full accommodation, transportation, artist materials and equipment to the selected artists. The SCCA’s intention was to attract mainly young and fresh graduates of local art schools, but also more mature artists, and encourage them to work in what was at that time only beginning to be called “contemporary art.” In Moldova, like in other states and republics of the former USSR, the latter was recognized and distinguished from the traditional fine arts by the range of new artistic media: video or computer art and photography, ephemeral art forms such as performance, happening and other body-related artistic practices, installation, and land art. On a more pragmatic level, the main and most urgent aim of this camp was to prepare the local artistic community and its audience for the first annual exhibition of the SCCA Chișinău, planned to open in the fall of the same year (see next case study The 6th Kilometer). This annual exhibition was regarded as the most important annual event, with a dedicated budget line and assigned key personnel, for most of the contemporary art centers established by the activist billionaire George Soros throughout postsocialist Eastern Europe.

Moldovan artists’ encounter with what began to be known at the time as “contemporary art” was somewhat different from that of their colleagues in other Central and Eastern European countries, though still comparable to the situation in other capitals of the former USSR where the SCCAs began their activities in the mid-1990s. What made the Moldovan encounter unique lay in the relation of contemporary art to modernism, high modernism and postmodernity, or what socialist art histories once called “non-conformism” or “unofficial art.” Moldovan semi-unofficial art (represented by such painters as Mihai Grecu, Eleonora Romanescu, Andrei Sârbu, Mihai Țăruș or Iurie Horovschi, and many others) reduced itself primarily to the fine arts. Even those who soon emerged to be called contemporary artists – above all Mark Verlan, but also to a certain degree the artists of the exhibition Căutări [Search] 90, Ștefan Sadovnikov, Igor Scerbina or other members of the Fantom group – were for the most part painters. Their aesthetic resistance to socialist realism was formulated primarily in pictorial terms, and “post-medium” works were rare, or at best undocumented and as yet unresearched (with exception of Mark Verlan). In other Eastern European countries, and in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Tallinn or Riga, by contrast, the newly formed Soros and non-Soros centers for contemporary art built upon the heritage of the rich local socialist unofficial art scene made official after the fall of the Berlin Wall (employing, for instance, the former “unofficial” art historians as the first art managers, curators and directors of their SCCAs). In Moldova – along with a few other countries or republics of the USSR – the Soros center played a more crucial role, serving as a jump starter for processes of modernization of local artistic discourse and practice.

The main task of CarbonART 96 camp was to spur and inspire the young artists by offering them information on available technological and material possibilities for the production of radically new forms of art, or to put it simply, the sort of artworks that could not be seen at the time in Chișinău’s main exhibition spaces. The SCCA Chișinău provided, first of all, video and photo equipment and every other form of material that was requested by the artist, as well as transportation, full accommodation and food; Western art magazines such as Artforum, Art in America, Parket, Texte zur Kunst, as sources of inspiration; and knowledge in the format of a series of seminars, including one led by the video art curator Hugo van Valkenburg on the history of video art in Holland, and one by the local art critic Constantin Ciobanu on the concept of the “open work,” as described in Umberto Eco’s 1962 Opera Aperta, drawing a comparison with Karl Popper’s vision of the “open society” in his 1945 book of the same title.

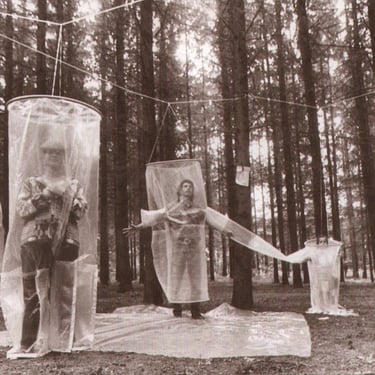

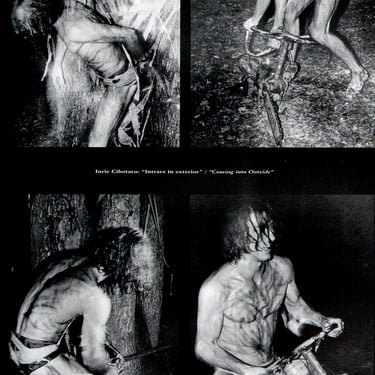

What it was that the curator and the organizers set themselves to accomplish was incorporated in the name of this artist retreat. Quoting from the Romanian Encyclopedia, and turning towards natural sciences, they chose one of the most abundant chemical element in the universe, carbon, which “forms more compounds than all the other elements combined,” to inspire artists to make “natural” works of art (for example land or earth art) and to pay closer attention to the processes of art-making. The title was also mean to evoke carbonization, hinting at artistic forms seen not as enduring objects but as perishable and ephemeral artistic gestures. Art could be seen not as the production of objects but of processes, behaviors, attitudes, and their recording through video or photographic documentation.

CarbonART 96’s reception evinced controversy. While embraced and welcomed by many local critics as an efficient means of modernizing of local artistic discourse by having it join (after half a century of Soviet isolation) the “progressive forces” on the globe, CarbonART 96 was criticized by “conservative” or nationalist intellectuals, and most forcefully by the Sadova peasants who for three weeks had to witness people of all ages and genders running naked through their forest and backyards. The socilaists and conservatives saw in this event the internationalization of American corporate interest (“selling Xerox machines under the pretense of freedom of speech”) or a direct intervention in if not a cultural contamination of traditional values with grant money offered by a financial speculator. For the organizers, CarbonART 96 became one of SCCA Chișinău’s longest running projects, and was held every summer up until the mid-2000s. Over this time, the curator and the SCCA witnessed the process of natural selection leading to the formation of a local contemporary art scene: from an initially homogenous group of artists, only a few took contemporary art seriously, embracing a new medium and practice and systematically questioning existing practices, taking English language courses, or learning the secrets of self-promotion and grant writing. The rest of the participants resisted this temptation, withdrawing back into fine arts (ceramics, tapestry, the good old canvas and paint) or design. The Soros Center (while it was fully funded) was itself seen with suspicion as a “nest,” to use a local idiomatic expression, that channeled grants to a few artists only – to those known as “contemporary artists” who traveled abroad to present the success of the postsocialist transition or democratization to a select Western public. The center itself was often perceived as a “foreign” cultural institution that did not serve local cultural interests.

Fragment from "CarbonART 96 and The 6th Kilometer, SCCA Chișinău 1996" in Esanu, ed. Contemporary Art and Capitalist Modernization.