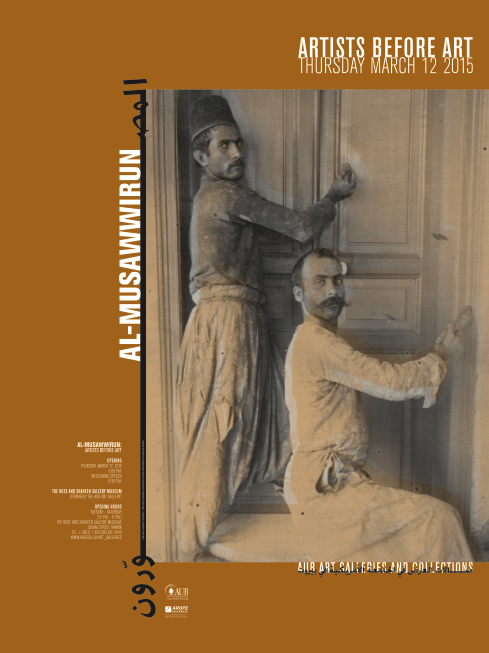

Al-Mussawirun: Artists before Art

SPRING 2015 (AUB Rose and Shaheen Saleeby Museum, Beirut)

This exhibition recreates, or simulates – within the restricted space of the university gallery – a landscape of images, pictures, and crafted objects that one might have come across a century ago in the area that includes present-day Lebanon. We catch a glimpse of a time when the Western model of autonomous art had not yet fully emerged in the Middle East, that is to say a time when there were no contemporary art centers and private galleries, art schools and museums, biennials, prizes, prices, dealers, critics and curators. We invite our visitors to imagine a cultural period in which very diverse modes of picture- and object-making, both utilitarian and non-, cohabited the same cultural field.

With the unfolding of modernity, the Arab Orient has seen a sharp increase in images. This proliferation of images came about through new techniques of representation and reproduction: from figurative and naturalistic conventions learned by Arab painters in the European fine art academies, to the rise in popularity of photographic and cinematic images. At the turn of the 20th century, Western techniques of representation contributed to the emergence of vernacular forms that blended local and foreign pictorial conventions. It was also during this period (the late 19th and early 20th century) that traditional Islamic art – which historically did not concern itself with the representation of nature but mainly with shaping everyday ambience – was gradually overtaken by a Western art preoccupied since the Renaissance with the representation of man and nature. A new hierarchical model of culture, with its schemata of high and low, fine and decorative, began to take shape. Western processes of modernization and industrialization played a crucial role in the marginalization of Islamic traditional arts. Western machine, in other words, replaced Islamic craft.

Al-Musawwirun: Artists before Art envisions a landscape of pictures and objects that coexisted prior to their modernistic division into “fine" and “decorative" or “material culture." The exhibition puts on display artifacts found today in Lebanon but produced all over the region between the second half of the 19th century to the mid-20th century. It is a landscape in which pictures – ranging from Christian iconography to traditional Islamic arts and vernacular or folk art and from Orientalist tableau to photographic and cinematic representations – were distributed within one cultural field in accordance with ethnic, kinship, religious or class divisions. Those who worked within this field were known by various names. In addition to artistes and fannanun (artists), or rassamun (painters), the most employed word was musawwir—a term used from ancient times to refer first of all to one of the hypostases of God as giver and shaper of forms, fashioner and creator, and by extension, to all those engaged in religious or folk arts. Historically the word musawwir was used mainly to refer to the work of the painter (in particular the portrait-painter) but it could also mean decorator or sculptor, less often architect or alchemist, and in the modern age photographer and cameraman. The subtitle “Artists before Art" is meant to suggest that a rich, viable, and self-sustaining alternative existed prior to the rise of the Western autonomous art model, with its institutions that maintain and reproduce capitalist production and exchange.

It is this diluvial world inhabited by odd, marginal and often extinct forms of art-making that we have selected for display. In addition to works from the first generation of Lebanese painters, most of whom traveled to Europe to learn Western pictorial conventions and to later become “pillars" of Lebanese art, we show works by musawwirun who did not study in Europe, as well as works by anonymous artisans working at the crossword of traditions and religions, of early photographers and cinematographers, and of foreign artists who passed by or settled in Beirut, seeking a name or fleeing bloody revolutions in a world that desperately wanted to become modern.

Octavian Esanu

Download Publication